Ha’Azinu | הַאֲזִינוּ: Deuteronomy 32: 1-52

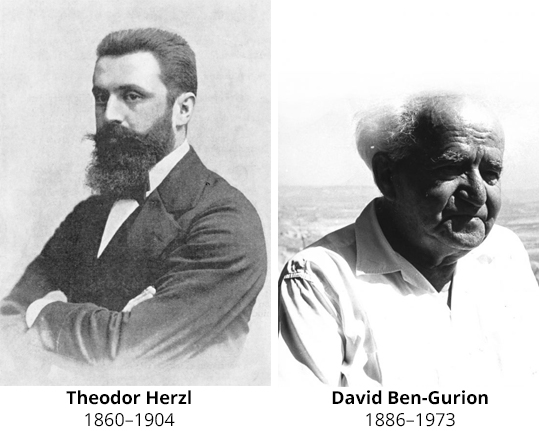

I have always had a fascination with books. My home, my desk, my office—all piled high with those I’ve read and those I look forward to reading. Not long ago I finished a biography of Theodor Herzl by historian Amos Elon and immediately pulled a second Herzl biography from my shelf to keep on my nightstand, at the ready, for the next moment of inspiration. For reasons I can’t quite explain, this second biography was among the books I brought with me to Israel for my month-long sojourn over the High Holidays, during which I look forward to seeing my sons.

Janet, my wife, and I chose Sde Boker | שְׂדֵה בּוֹקֵר as the place to pass our two-week quarantine and the unexpected national lock-down in the face of rising numbers of COVID-19 cases. Sde Boker is the small desert community in the Negev to which Israel’s founding father and first prime minister, David Ben-Gurion, retired from public life. It is also here that he chose to be buried on a plateau overlooking the Wilderness of Zin | מדבר צין from which the Children of Israel finally emerged into the Promised Land following 40 years of wandering in the desert after the Exodus.

Ben-Gurion was particular about the location, and his decision not to be laid to rest alongside his life’s inspiration, Theodor Herzl, on the Jerusalem peak that is home to the national cemetery bearing Herzl’s name. Ben-Gurion was convinced that the nation’s future would be tied to its ability to conquer—to harness—the desert. He also believed that the single most significant act of his own remarkable life was to have come to the Promised Land at the age of 20 in 1906—to have made Aliyah. In fact, the date of his arrival is the only thing etched on his gravestone other than his name and the years of his life. He knew that by making this choice, many would come to the Negev to visit his grave and once there, would be confronted by the juxtaposition of the biblical rebirth of Jewish sovereignty and the fulfillment of Theodor Herzl’s modern Zionist dream.

Ben-Gurion was particular about the location, and his decision not to be laid to rest alongside his life’s inspiration, Theodor Herzl, on the Jerusalem peak that is home to the national cemetery bearing Herzl’s name. Ben-Gurion was convinced that the nation’s future would be tied to its ability to conquer—to harness—the desert. He also believed that the single most significant act of his own remarkable life was to have come to the Promised Land at the age of 20 in 1906—to have made Aliyah. In fact, the date of his arrival is the only thing etched on his gravestone other than his name and the years of his life. He knew that by making this choice, many would come to the Negev to visit his grave and once there, would be confronted by the juxtaposition of the biblical rebirth of Jewish sovereignty and the fulfillment of Theodor Herzl’s modern Zionist dream.

Herzl’s Zionist career spanned just nine years. An accomplished journalist and playwright, he was deeply affected by rising antisemitism in his hometown of Vienna and by the spectacle of the Dreyfus Affair in Paris, which he had covered as a correspondent for Vienna’s Neue Freie Presse. Completely unaware of Zionist thinkers who had preceded him (among them Moses Hess and Leon Pinsker), he began a nine-year odyssey to secure a modern homeland for his beleaguered people. His vision and tireless determination would bring him into negotiations with heads of state of Germany, Austria, Italy, and the Ottoman Empire, as well as with Pope Leo XIII, the Rothschilds, and countless other senior officials and Jewish leaders across Europe. He convened the First Zionist Congress in Basle, Switzerland, in August 1897, at which he founded the modern Zionist Movement. On the final day of that first Congress, he wrote this entry in his diary:

“If I were to sum up the Basle Congress – which I shall not do openly – it would be this: at Basle I founded the Jewish State. If I were to say this today, I would be greeted by universal laughter. In five years, perhaps, and certainly in fifty, everyone will see it. The State is already founded, in essence, in the will of the people to the State.”

Herzl died of heart disease in 1904 at the age of 44. The movement he founded inspired Ben-Gurion to come to Palestine two years later, where in May 1948, he fulfilled Herzl’s prophetic diary entry, declaring Israel’s independence, almost exactly 50 years later.

On the flight to Israel last Thursday night, I began that second Herzl biography, “Theodor Herzl, Founder of Political Zionism,” published in 1959 by historian Israel Cohen, a participant in the Second Zionist Congress in 1898. Inside the cover, I noted the handwritten name, Melvin Goldstein. Melvin, z”l, had an extraordinary career as a Jewish professional, serving for many years on the senior staff of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee. I was privileged to know his widow, Lolita, z”l, who passed away in 2016 at the age of 99. Lolita and I had worked together to continue the pursuit of Ben-Gurion’s vision for the Negev through the university that bears his name. Ben Gurion University of the Negev’s desert research campus here in Sde Boker, also houses his personal archive (his presidential library). Lolita and Melvin had no children. Over the course of their life together, they amassed a remarkable library chronicling the last century of our people’s history. Following Lolita’s death, her niece made a gift to me of a number of these books, among them Israel Cohen’s “Theodor Herzl,”—a precious keepsake of a treasured friendship.

On the flight to Israel last Thursday night, I began that second Herzl biography, “Theodor Herzl, Founder of Political Zionism,” published in 1959 by historian Israel Cohen, a participant in the Second Zionist Congress in 1898. Inside the cover, I noted the handwritten name, Melvin Goldstein. Melvin, z”l, had an extraordinary career as a Jewish professional, serving for many years on the senior staff of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee. I was privileged to know his widow, Lolita, z”l, who passed away in 2016 at the age of 99. Lolita and I had worked together to continue the pursuit of Ben-Gurion’s vision for the Negev through the university that bears his name. Ben Gurion University of the Negev’s desert research campus here in Sde Boker, also houses his personal archive (his presidential library). Lolita and Melvin had no children. Over the course of their life together, they amassed a remarkable library chronicling the last century of our people’s history. Following Lolita’s death, her niece made a gift to me of a number of these books, among them Israel Cohen’s “Theodor Herzl,”—a precious keepsake of a treasured friendship.

Tomorrow we come to one of the last portions of the Torah: Ha’Azinu. In it, Moses delivers his final address to the people as they make ready to enter the Promised Land, a journey he would not make with them. Instead, he ascends Mount Nebo, and from its peak, he sees the path before them, a path through the Wilderness of Zin.

Our lives flow with the currents of time—across years, centuries, and millennia of Jewish history. Inevitably, now and then, these currents bring seemingly disparate threads together, creating extraordinary moments of beauty and power that seem only to have been made possible by the hand of the Almighty. Amidst these incredibly unusual first days of 5781, I find myself not far from the place where Moses bade farewell to the generation of Jews who would restore sovereignty to the land promised by God to Abraham, very near the gravesite of David Ben-Gurion, whose life was inspired by Theodor Herzl’s vision. It is here that I read the final pages of a Herzl biography, given to me as a symbol of a friendship borne of shared commitment to the fulfillment of Ben-Gurion’s dream.

Ha’Azinu| הַאֲזִינוּ | Listen—the voices of history call out to you. And every now and then, if you listen carefully enough, you can hear them.

Shabbat shalom | שבת שלום and g’mar chatima tova | גמר חתימה טובה

Doron Krakow

President and CEO

JCC Association of North America

Reader Interactions