By Leah Garber

This is the time to act the most holy we the Jewish people have ever acted in our history.

This is the time to do something out of the ordinary, the likes of which have never been seen in any people’s history. Now is the time to save 133 innocent souls for no other reason except that it is holy, and it is the most Jewish response to October 7 that can possibly be done.”

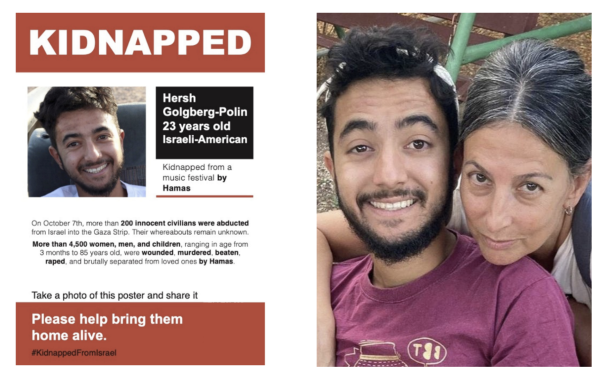

– Rachel Goldberg-Polin, mother of 23-year-old Hersh Goldberg-Polin, who was kidnapped from the Nova Music Festival on October 7

For 195 days, Rachel Goldberg Polin, the mother of Hersh, who was kidnapped from the Nova Music Festival, has not let up her fight. Rachel has become one of the most prominent activists in the international struggle for the return of the hostages who remain in Gaza. She has met with a series of leaders, spoken at the United Nations, and, most recently, been named one of TIME’s 100 most influential people. Rachel’s life turned upside down on October 7 and has remained so for 195 days. When she turned on her phone that day, two messages awaited her from Hersh: “I love you,” followed by “I’m sorry.” Only later did she realize that her son had been kidnapped to Gaza from the Nova Music Festival and that his left hand had been blown off in the attack. Since then, she has been fighting tirelessly for the release of Hersh and the other hostages from Gaza.

On Monday evening, millions of Jews around the world will gather around festive Pesach Seder tables. As we do every year, we will read the Haggadah, learn about the Israelites hardships in ancient Egypt, and praise the miraculous redemption, following 400 years of cruel slavery. We also will mark the turning point in our collective Jewish history at Mount Sinai, where we not only received the Torah—our Jewish code of conduct and theological textbook—but also became a people.

The young ones in every family will sing Mah Nishtana | The Four Questions, asking why this night is different from all other nights. Unlike in other years, however, this year we will not have the usual answer.

Everything has changed, and it’s all so painfully different.

Much has been said about how much Israel has changed since October 7. We will never be the same country again, nor the same people—collectively or individually. The terrible massacre has scarred us in a way that will never truly heal.

Our Seder tables will have an empty seat, representing the 133 souls who will not mark the holiday but rather the fact that by Pesach, they will have been buried alive in the darkness of Gaza’s tunnels for 200 days. They won’t tell the stories of slavery, hardship, or suffering endured by our ancestors because they live these horrors day by day, hour by hour. Their “Moses” is delayed; their redemption is suspended. There is no need for them to cross the sea and walk between walls of water for redemption. After all, home is so close, yet so far away. Sadly, we will gaze at the empty seats and repeat Moses’s demand of Pharaoh on their behalf: “Let my people go! Let our people go!”

This year Pesach, the Festival of Freedom, will remind us more than ever that our freedom is challenged time and time again. We will recite from the Haggadah: “For not only one (enemy) has risen up against us to destroy us, but in every generation, they rise up to destroy us,” and we will pray that as in the past, “The Holy One, Blessed be the Eternal, delivers us from their hands.”

We will be tormented by the desire to rejoice with our own families and with tremendous gratitude for what we have and by the incessant pain that clings to our flesh and does not let go. We will be torn apart by the festivity that Pesach offers and the painful absence that will be so present on this night, most particularly in 133 Israeli homes.

We will close our eyes and think sadly of the tables around which new orphans, widows, and bereaved parents sit; we will cry for so many children who are not asking Mah Nishtana, but rather where is Abba?

We will pray for the safety of the thousands of wounded, some of whom are in a continuous, Sisyphean rehabilitation process and some of whom are adapting to the reality of a new disability.

And we will hope that the tens of thousands of families who sit at Seder tables in hotels or temporary apartments—with no homes in which to celebrate—can return home safely and quickly.

On Pesach this year we will almost apologize for daring to greet each other with “Happy holiday.” We’ll look down and realize it can’t really be a happy holiday. Maybe just a holiday.

Nature does not consider emotions; it is indifferent to the mood; and does not bother to adapt itself to our mindset. Nature is stubborn, consistent, and continues in its own way.

Pesach, also known as the holiday of spring, heralds the coming of the season of renewal, blossoming, growth. It’s almost unbearable to look at all the beauty that nature offers, generously. The gloom of winter would be more appropriate, reflecting the nature that has taken over our hearts, even if not the fields.

“It’s not the same valley, it’s not the same house

You are gone and you will not be able to return.

The path with the boulevard, and an eagle in the sky

But the wheat grows again.

And how it happened and how it is still happening.

that the wheat grows again.”

– Dorit Tzameret, “The Wheat Grows Again”

From the bottom of my broken heart, I pray for a miracle that will bring all the hostages, all our people, back home to their families by Seder night.

Together, united, we will overcome.

Leah Garber is a senior vice president of JCC Association of North America and director of its Center for Israel Engagement in Jerusalem.