By Doron Krakow

Rushing In

This morning I made my way back to the United States—the High Holidays nearly behind us, and so many extraordinary opportunities in the New Year, now underway, beckon back in New York. Yesterday, before packing for the trip, I went to meet friends for coffee on Rechov Bograshov (Bograshov Street) in Tel Aviv. While waiting for a table at a local café, I witnessed a frightful accident when a car, crossing Bograshov, knocked into a scooter—the driver clearly didn’t see—that was carrying two boys. As the car screeched to a halt, the scooter and the boys went flying.

Thankfully, the story had a happy ending. Having apparently suffered no serious injury, the boys soon got back on their scooter, which was dinged up but without major damage, and, like the driver of the car, continued on their way.

For a while, though, it looked as if it was going to be much worse. The crash. The cries of the boys. A moment of panic. And then, it happened. An instant later, they came running from every direction. Pedestrians. Café waitstaff. Customers and shopkeepers from nearby stores. A bus stopped abruptly, and the driver ran to the scene, as did the driver of the car that had struck the scooter. They all rushed to lend a hand. To help those boys.

I was thinking about what I’d seen when I heard another story with a similar theme.

A person close to me had some major surgery this week. She, her husband, and three young daughters live in a small village of perhaps 250 families in Israel’s north. She was in the hospital for a few days and returned home for what likely will be a lengthy recovery. The village has a committee of sorts to provide help and support at such times. Without having been asked, its members arranged for the family’s house to be cleaned and began organizing meals and activities for the kids.

These certainly aren’t the stories we typically read about in the news. Politics in Israel, the U.S., Canada, and elsewhere have become so polarizing and so contentious that every incident, it seems—consequential or not—becomes fodder for division, outrage, and opprobrium. In this environment, it is altogether too easy to become dispirited about the state of our nations and our sense of community.

That’s a shame because who and what we are is so much more. We grew up in societies predicated on good citizenship, service, shared ambitions, and aspirations—a commitment to g’milut chasadim | גמילות חסדים, acts of lovingkindness. Hardly perfect, our communities are, nonetheless, ever striving to be more than what they are. In our zealousness to call out those aspects that fall short of our individual or shared expectations, we run the risk of looking past so much that is good.

The High Holidays—Rosh Hashanah | ראש השנה, Yom Kippur | יום כיפור, and Sukkot | סוכות—are weeks of reflection, of atonement, of forgiveness, and of celebration. They are our companions in these, the first days of the New Year. They remind us of who we are and of our responsibilities to and for one another. They mark a new beginning and a chance, once again, to be and to become our best selves. To rush in when others are in need. To stand with and behind those with whom we share community and peoplehood—even in the face of difference and debate. To acknowledge all that we, as a nation, and a people, have become—without losing sight of all we have yet to achieve.

The final days of this year’s High Holiday season—marking Sh’mini Atzeret | שמיני אצרת, celebrating the arrival of the rainy season in Israel and acknowledging rain as the source of fresh water and new life, and Simchat Torah | שמחת תורה, when we end one cycle of Torah reading and start a new one—are now upon us. I wish you, once more, a chag sameach and a shanah tovah.

Shabbat shalom | שבת שלום

Doron Krakow

President and CEO

JCC Association of North America

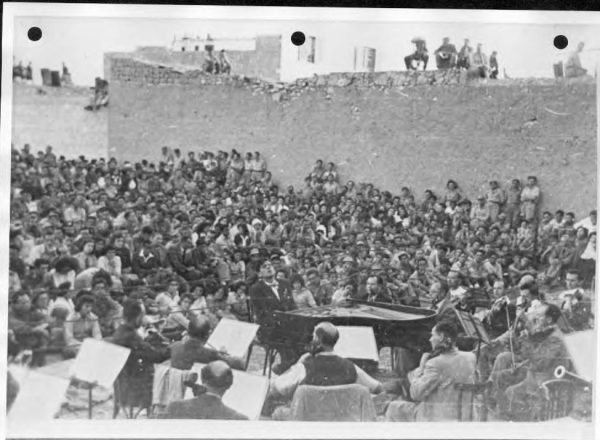

On October 5, 1948, Leonard Bernstein was given a huge ovation when he opened the first-ever season of the Israel Philharmonic at Ohel Shem Hall in Tel Aviv. The program that evening, attended by luminaries from Israel’s political, cultural, and diplomatic communities, was devoted entirely to Beethoven, and Bernstein himself performed the piano solo in Piano Concerto No. 1. Many in the orchestra were refugees and survivors of the Holocaust who had made the new State of Israel their home.

On October 5, 1948, Leonard Bernstein was given a huge ovation when he opened the first-ever season of the Israel Philharmonic at Ohel Shem Hall in Tel Aviv. The program that evening, attended by luminaries from Israel’s political, cultural, and diplomatic communities, was devoted entirely to Beethoven, and Bernstein himself performed the piano solo in Piano Concerto No. 1. Many in the orchestra were refugees and survivors of the Holocaust who had made the new State of Israel their home.

And that’s the way it was…

Reader Interactions